A new way of anchoring individual iridium atoms to the surface of a catalyst increased its efficiency in splitting water molecules to record levels, scientists from the Department of Energy's SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and Stanford University reported today.

It was the first time this approach had been applied to the oxygen evolution reaction, or OER –part of a process called electrolysis that uses electricity to split water into hydrogen and oxygen. If powered byrenewable energy sources, electrolysis could produce fuels and chemical feedstocks more sustainably and reduce the use of fossil fuels. But the sluggish pace of OER has been a bottleneck to improving its efficiency so it can compete in the open market.

The results of this study could ease the bottleneck and open new avenues to observing and understanding how these single-atom catalytic centers operate under realistic working conditions, the research team said.

They published their results today in theProceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Industrial backbones

Catalysts are the backbone of the chemical industry and hold promise for a sustainable energy future. Like matchmakers, they grab molecules from a passing flow of liquid or gas and encourage them to react with each other, without being consumed themselves. To maximize the efficiency of this process,catalyst nanoparticlesare typically scattered on the surface of a porous material that offers the largest possible surface area for many reactions to take place simultaneously.

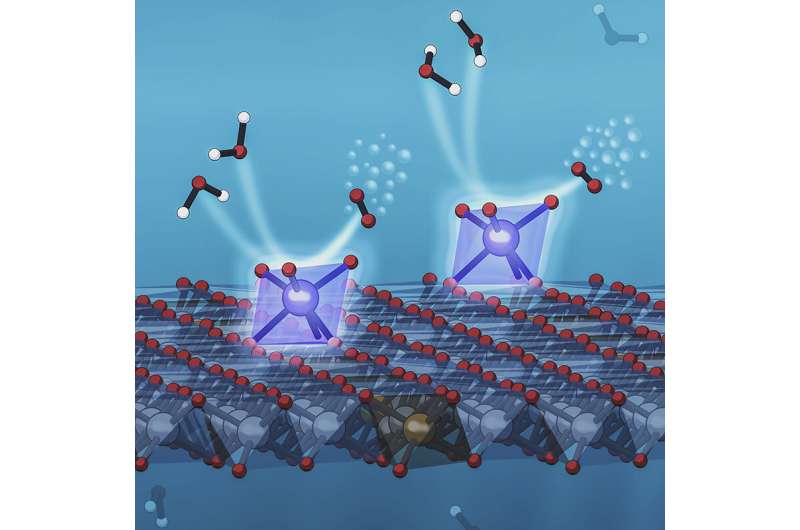

But only the atoms on the outside of a nanoparticle can participate in catalysis; the inner ones go to waste. When thecatalystis a pricey precious metal like iridium or platinum, even a small amount of waste is expensive. So scientists have been working on using individual atoms of these precious metals instead. Each atom is a catalytic reaction center. Their tiny size means a lot more of them can fit on the surface of a given support structure. This greatly increases the amount of active catalyst that's exposed to the reactants and the number of reactions that can take place at once, boosting efficiency.

In this study, a team led by SLAC/Stanford Professor Yi Cui and SLAC staff scientist Michal Bajdich developed a new way to anchor individual iridium atoms on a supporting surface. Stanford postdoctoral researchers Xueli Zheng and Jing Tang carried out the experiment, aided by theoretical simulation of X-ray data from SLAC associate staff scientist Alessandro Gallo that revealed which configuration would be the most stable and effective.

Atom-by-atom anchoring

To make the new catalyst, researchers first made a porous structure to support the iridium atoms that would catalyze the reaction.

They exposed this foam-like structure to a solution containing iridium compounds, quickly froze it to create a thin, iridium-rich layer of ice on the surface, and did additional processing to create well-distributed sites where individual iridium atoms were snugly anchored on the supportive surface.

X-ray observations of the catalyst at work revealed that the iridium atoms were in a chemical state that makes them exceptionally effective in carrying out the part of the water-splitting reaction that releases oxygen.

Other tests showed that this enhanced activity was due entirely to the fact that the iridium was in the form of single, isolatedatoms, and not just to the largesurfacearea on which they were embedded.

The resulting catalyst is better than most of theiridium-based catalysts known to date, the researchers reported. They said this new atom-anchoring system provides an ideal model for probing and establishing the connection between catalysts and their support structures for a variety of electrocatalytic reactions.